By George Gilson

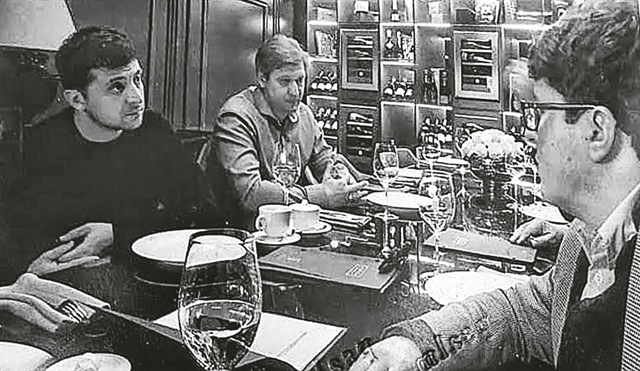

It was on the eve of the first round of the Ukrainian presidential election, held on 31 March, 2019, that journalist and author Vladislav Davidzon, a non-resident fellow at the Eurasia Center of the Atlantic Council, and some friends of his organised a dinner for then presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelensky, who in the second round one week later swept to power in a landslide, garnering 70 percent of the vote.

The atmosphere was clearly so convivial that the conversation lasted three hours, with famed French public intellectual and prominent member of the influential, mid-1970’s “Nouveaux Philosophes” (New Philosophers) movement Bernard-Henri Lévy, and Olexander Danylyuk (who soon would serve as Zelensky’s Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council and was Davidzon’s connection with the future president) participating in the political symposium.

Davidzon, who lives in Paris and maintains access to Zelensky’s staff but is not an advisor, has family links to both sides of the Russian-Ukrainian war, as he is married to a Ukrainian woman, is the son of a Russian-Jewish father and a Ukrainian Jewish mother, and has spent quite a bit of time in both countries.

The impressions of the seasoned journalist – who when he asked Zelensky whether he was a populist received an answer of feigned confusion over the definition of the word, “What do you mean, what’s that?” – reveal the Ovidian transformation of an unprepared and somewhat frightened businessman-actor into a leader who has conducted with immense success an international and quite audacious campaign to defend the territorial integrity and distinct cultural heritage of his country. He offers fascinating insight into the personality of the man who has been the focus of unprecedented global public attention.

Davidzon discerns an ideological kinship between neo-imperialist, expansionist Russian President Vladimir Putin and his close ally, neo-Ottoman and expansionist Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has persistently challenged Greece’s sovereign rights and maritime zones.

He squarely dismisses criticism that Zelensky is acting as an American pawn in a post-Cold War US-Russia struggle for regional hegemony.

The journalist and author also rejects the notion that the Ukrainian president may be beholden to domestic financial interests, including his main backer in the election that swept him to power, top oligarch and media owner Ihor Kolomoysky, once ranked as Ukraine’s third richest man and now worth one billion dollars according to Forbes.

Kolomoysky’s television channel aired the immensely popular series “Servant of the People”, a prophetic political satire comedy (which was Zelensky’s specialty as an actor, digging into the country’s previous leaders), in which he played a high school teacher who unexpectedly becomes president of Ukraine thanks to a video that went viral. The channel later played a key role in ensuring the current president’s success.

Davidzon underlines that Zelensky has long distanced himself from his erstwhile patron.

Undoubtedly, he had very good reason to do so.

In an investigative report by Casey Michel, author of American Kleptocracy, and entitled “Who is Ihor Kolomoisky?”, published on 13 March by Britain’s venerable The Spectator, the world’s oldest weekly magazine, it emerges that the oligarch’s extremely shady financial dealings extended all the way to, of all places, Cleveland, Ohio.

“As investigators and authorities now know, one of the most notorious oligarchs out of the former Soviet space oversaw a trans-national money laundering scheme of historic proportions – and used places like Cleveland, in addition to a number of other small towns across the American Midwest, to hide and launder hundreds of millions of dollars. With no one paying attention, this oligarch, a Ukrainian national named Ihor Kolomoisky, steered one of the biggest Ponzi schemes in world history, and ended up becoming one of the biggest real estate landlords in mid-west America,” the article stated.

Nothing directly links Zelensky to all of that, and Davidzon’s keen grasp of both Ukrainian and Russian politics sheds light on how the one-time actor and businessman earned the world’s immense admiration and support for his success in rallying his people in their struggle to defend their independence, freedom, and cultural identity, and on the reasons for his amazing success to date in facing down, like a latter-day David against Goliath, the fascistic invader Vladimir Putin.

Tell me a little bit about yourself.

I’m Ukrainian-American, born in Uzbekistan, grew up in Brooklyn. I had a Russian passport as I lived in Moscow in the 90s, but have burned it in protest at the acts of the Russian army. I live in France now with my Ukrainian wife. I am resident fellow at Eurasia Center of the The Atlantic Council and Author of ‘From Odessa With Love’ a book about Ukraine and Odessa between 2013-21. I commuted between France and Ukraine before all this began, but that commute has become quite a bit harder in the wake of the Russian invasion.

What’s going on in Ukraine now and what do you see happening?

The war has been going on for several months and the Ukrainians have won the battle of Donbas, with the Russians having pulled out of all the territory that they had occupied around the Ukrainian capital. After several weeks worth of a reprieve, the Russians have adjusted their war aims and announced that they are interested primarily in taking the East and South of the country. They will have tremendous issues with their advance in the south. We are watching artillery battles take place in Kyiv at this moment, though the actual Russian assault currently is quite tepid.

In the ongoing propaganda war, which is an integral part of all wars, one wonders if the Ukrainian resistance against the powerful Russian war machine is being blown up to persuade the world that it is not a lost cause.

Look, the Ukrainians are fighting on home turf. They have very high morale. They are defending their own territory. Putin over-extended himself. He really thought that the Ukrainian nation doesn’t exist as a state or as a peopLe. He really thinks that Ukrainians and Russians are the same people – that the Ukrainians are at best confused and at worst under the auspices of propaganda. He just basically doesn’t believe in the existence of the Ukrainian state. But the Ukrainians do and they are willing to die for it, which is the test of whether a country exists or not. Russia and Ukraine are two different nations with different character traits and mentalities. The Ukrainian willingness to resist has objectively outperformed all intelligence projections about how much they were willing to do. The fearsome Russian war machine turned out to be creaky, badly oiled, broken down and uncoordinated.

What are those differences in the Ukrainian and Russian mentalities?

The Ukrainians are more independence-loving, more anarchic. The Russians are more centralised, more authoritarian. The Ukrainians are personally less arrogant than the Russians. They have less of this grandeur and imperial pomp. That’s one big difference. Russians are more straightforward in their negotiation style, whereas Ukrainians are a little bit more wishy-washy – let’s do this, let’s do that – in my experience. Ukrainians are more liberal. Russians are harsher in some ways. These are broad generalisations, but there are psychological differences.

Also there are a lot of Ukrainians in Russia. The biggest Ukrainian diaspora is not in Canada or America. There are about three million Ukrainians living in Russia. There are a couple of million Russian-speaking people in Europe. So the demarcation lines of the borders are not exact. Many of those living eastern Ukraine like Donbask are more like Russians than Ukrainian, though again that is a generalization. Ukrainians have lived under Russian occupation and along with Russians for centuries so some character traits are very similar.

What do the Ukrainian and Russian peoples each believe they have in common?

Languages and the Church. But there are also a lot of inter-marriages. I’ve read a statistic that every third Russian has relatives in Ukraine, which makes all the more horrible what the Russians are doing in Ukraine. When people say brotherly nations, that’s Russian propaganda, but they are cousins in a way.

What is your sense of the pulse of how the Ukrainian people feel about the Russian people right now?

I think that what we saw happen at Bucha and Irpin was a turning point. I think the bitterness and trauma will last generations. The rage toward Russia is understandable after the killing of tens of thousands of Ukrainians has taken place.

What percentage of the Russian people do you think share Putin’s imperialist dreams?

Maybe half, maybe somewhat more.

Do you think the war will increase or decrease that percentage?

It’s hard to say what the Russians actually know, because they have very little access to real information. They don’t know what’s going on here. They blocked Facebook in Russia. That’s a big deal. There is no more contact between Russians and Ukrainians on Facebook, but anyone who wants to know what is happening will know by now.

Many in Greece view Putin’s irredentist expansionism as parallel and similar to the neo-Ottomanism of Erdogan. Would you agree?

That seems about right to me. We are living in an illiberal, revisionist moment, when the American-led liberal democratic consensus – American hegemony or liberal world order or post-Cold War consensus, or whatever you want to call it – after WWII is collapsing. The old consensus is over one way or another. This conflict is the nail in the coffin for that order. We’re back to something different. The Chinese, the Russians, and the Turks are revisionist powers and they’re on their way up, as Americans and Europeans are on their way down. Yet the collective response of the West has been collectively impressive enough to make us think that the West has not been beaten yet.

How authentic and durable is the Putin-Erdogan ‘friendship’? Is it a shaky marriage of convenience, or is it something deep that they can geostrategically and militarily cooperate on in the longer run?

It’s not a friendship. It’s as you said a marriage of convenience on some issues, and on other issues they’re fighting on opposite sides. In central Asia, Iran, Armenia, and Azerbaijan it’s a marriage of convenience. On the other hand, in Libya, Syria, and Ukraine they are fighting on different sides or they have proxy soldiers on different sides. They talk to each other and it’s a flexible relationship, but they are not friends, and neither are they enemies. Ultimately, the Turks are still in NATO. They are more and more undemocratic but they are on our side and they have some big issues with Moscow, and they obviously have different issues than the Russians with Greece. In Libya, there is a proxy war between the Russians and the Turks. There were shooting conflicts between Russia and Turkey that they had to deconflict in Syria. So it is a complex relationship.

In November, 2015, the Turks downed a Russian war plane on their border with Syria and nothing much came of it, surprisingly. How does one explain that?

Putin backed down, because ultimately he is a bully. When you stand up to him, like the Ukrainians are doing now, he does not fight back. Ultimately, the Turks apologised in a wishy-washy way, but they got away with it. You’re absolutely right.

Have you met or do you advise President Zelensky?

I had dinner with him once, the day before he became president. That was the only time I interacted with him on a personal level, for three hours.

What was your impression? What kind of man did you meet?

I met a man who was understandably nervous, who was on the cusp of winning power. He knew that he was going to be the most powerful man in Ukraine. He was unprepared. He was bright and charismatic but badly educated on the issues. He was a little bit paranoid, but very good at figuring people out – he looked at you and tried to div you out psychologically. He was smart. He was psychologically intelligent, but he was not prepared for that job and he I think knew it. He’s a tough guy. He is very, very muscular and highly built. He is very male. He enjoys the company of men. He’s just masculine. He’s tough. He comes from an intelligentsia family. Both his parents are Jews, middle class engineer types – the father a math professor (he taught cybernetics and computer sciences in the ‘80s and ‘90s) and the mother is a retired engineer.

As a journalist, what questions did you ask him to which you found the answers surprising or perplexing?

I asked him if he’s a populist and he said, “What do you mean if I’m a populist? What do you mean, like what are you talking about?” I remember him shooting it down. He has governed as a moderate liberal in terms of his own political instincts.

Would you consider him a cultured person?

His sense of humour is very low brow, Benny Hill, Mad Magazine comic book. He’s not a highly cultivated guy in the high culture sense. He’s mass culture. He’s popular. The reason he is president is that he has a very deeply instinctual connection to the average Ukrainian. He is the average Ukrainian. He has a deep instinctual connection to the tastes, fears, interests and emotions of the average Ukrainian. He’s tough. He’s not highly educated or cultivated in the manner of someone with intellectual tastes. He is Muzhik, but he has a high sense of values is my sense.

There are those outside of Ukraine that consider him an American puppet.

He’s not an American puppet. He’s a guy who had a very tough learning curve, and any president of Ukraine will be very highly reliant on American political and diplomatic support. It was the same for Poroshenko and Yushchenko. Any president of Ukraine is going to be deeply reliant on the Americans and the Europeans. In fact, Zelensky was notably much less responsive to American concerns, and he didn’t care as much about what the ambassador said as Poroshenko did. That criticism is interesting, but it is not the case if you actually know what the relationship is internally. His people [associates] were much more independently-minded in the sense that they didn’t care as much.

Did he get elected with Jewish backing?

No. There is no such thing really… He had a single core oligarch and some other smaller supporters. The way you get elected in Ukraine – and I am Jewish myself -is that you have the backing of a single TV station. There are six major TV stations and if you don’t have one of them backing you you’re not going to get elected. The oligarch that helped elect him was [Ihor] Kolomoyski [one of the three richest men in Ukraine]. He’s not a puppet of Kolomoyski. People thought that he was. Kolomoyski was an investor in his company and he did help him with tv airtime, but Zelensky and his admin have since taken their distance from the oligarch.

Aside from a TV station you need a war chest to get elected. Did Kolomoysky provide that?

He provided some of it. Other oligarchs and businessmen – a consortium – contributed. Like every other presidential candidate in Ukraine he had an alliance of rich people backing him. He wasn’t the Jewish candidate, and now that he is in power he took his distance from Kolomoysky. He’s not psychologically or financially reliant on anybody. It was not like a Jewish conspiracy if that is the question.

How does the system of oligarchs work in Ukraine, as compared to Russia?

In Russia, the Kremlin captured the oligarchy and they are subservient to it. The oligarchs are allowed to do what they do economically as long as they stay out of politics. That’s the deal they had. In Ukraine, the centralised government was never strong enough to conquer the oligarchs, so six or seven oligarchs compete with each other and they have a lot of political power and TV power. Zelensky came in tried to sideline that system a bit but the war has broken that system in ways that we will not be able to understand until it is over.. He didn’t destroy it completely. They still compete with each other and they represent de facto a separation of powers. They compete with the state for resources. The war has sidelines all politics and oligarchic completion however. Wars are contingent situations.

Do you think that President Biden and NATO are partially responsible for developments in the sense that they might have done more to avert the invasion in advance?

In one sense, they were responsible as they actually had the intelligence and knew what was going to happen but were not able to keep this from happening by putting enough pressure on Putin. This isn’t about NATO. It’s about the fact that Putin cannot have an independent Ukraine. He just cannot deal with it. It’s a real existential threat to his regime. He’s been very clear. He wants to destroy the Ukrainian political nation. He wants to destroy the country.

Why does Ukraine represent a political threat to Putin?

It is because if the Russians see that the Ukrainians can build a liberal democracy and be rich and independent and get rid of corruption, they’ll want the same. The authoritarian regime that Putin has built is absolutely the opposite of the government that the Ukrainians have, and he sees them as an important part of the Russian Empire. There is no Russian Empire without the Ukrainian heartland. Secondly, he can’t deal psychologically with the fact that they are leaving his sphere of influence, and politically it is a problem for him.

But this has been going on for nearly a decade.

It’s been going on for a decade and he sees that the Ukrainians are slipping further and further away and he decided he could not deal with it any other way. The fact that he started a war is already proof of the fact that they were not able to solve this problem with diplomacy or anything else. This is already a desperate gambit.

A friend tweeted that part of the reason that Ukraine was not admitted to NATO is that it has always been clear that we would not go to war with Russia over Ukraine. Russia has called our bluff. The lesson is to never bluff again. That’s about right. Putin had a reputation for being a very cunning tactician, but on this question he is very emotional and so he went all out and gambled everything, including the entire Russian economy and potentially his rule, in order to ‘reunify’ the Slavic states of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine. He miscalculated terribly. A wise Greek from Odessa told me recently when I spoke to him that ‘some people become so entrapped in their emotions that they do not see a way out’. That seems right to me.

President Zelensky has conducted an historically unprecedented international diplomatic campaign with addresses not only to the UN but to a large number of parliaments. In each he pushes the hot buttons of national-ethnic emotions and makes demands such as the EU cutting off all procurement of Russian fossil fuels, despite the hardship that this would cause many countries.in terms of energy supplies and prices. The world hears much more from him than from President Biden, Jens Stoltenberg, and NATO leaders. Does he now view himself in some sense as the leader of the free world, casting himself in the role of a contemporary Churchill, to whom some have likened him?

Zelensky has a job to do and the Ukrainian state has only survived because of the disciplined communications. He sure is a much better and more serious communicator than Biden. I do not know what is happening inside of his head, but I do not think he sees himself as Churchill. Though he has certainly stood up in the moment and behaved admirably, keeping the nation together and leading with his example.

Why has Zelensky effectively closed the war to serious high-level diplomacy with Moscow now, choosing instead to attempt to cause major harm to the Russian army before negotiating?

The negotiations with Russia were fairly far along but collapsed when the extent of the killings in Buch and Irpin under Russian occupation became widely known. The extent of the barbarism in those towns and the number of people raped and mutilated and killed with summary shots to the back of the head only became apparent after those towns were taken back by the Ukrainian armed forces. The Ukrainian nation was understandably in no mood for negotiations when they saw what happened in those towns.