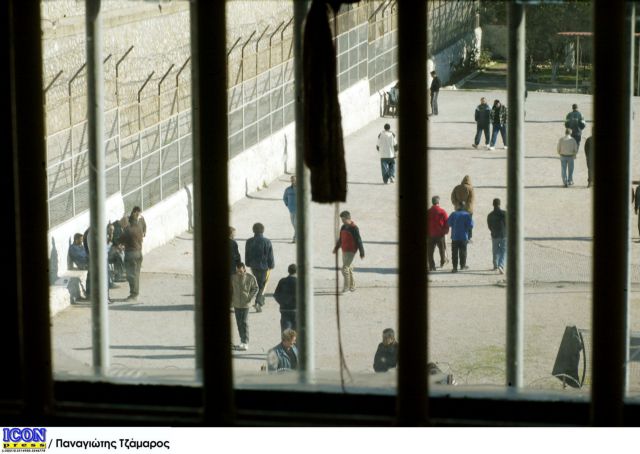

It is known that Greek prisons have been transformed into warehouses of people still standing trial and convicts. The practice of pre-conviction incarceration in the country has substantially inflated the number of prisoners, who in many cases live in conditions that are unacceptable for a state that is well ruled. The result is that they neither serve their correctional role, nor do they ensure the principle of innocent until proven guilty.

With the customary shoddiness with which it handles problems, the Greek state instituted – supposedly temporarily – the Paraskevopoulos law (named after the former justice minister who tabled it), in order to decongest prisons and shape better basic conditions of incarceration. Obviously because it was considered “successful”, its implementation was again extended, despite the fact that it caused a host of problems.

The result is the release of many prisoners with problematic criteria, who immediately after their release return to delinquency or criminal activity. At the same time, it is evident that an industry of prison releases, based on reasons of health or handicaps, has been set up, and is unfortunately commonplace in Greece.

It is indicative that, based on data presented to parliament by the justice ministry, in the 2015-2018 period, there were 341 prisoners released based on handicaps, out of whom 323 availed themselves of the provisions of the Paraskevopoulos law.

In the previous five years, 2009 to 2014, only 53 prisoners were released based on handicaps, but 85 percent of applications for release for health reasons were approved.

It is obvious, from the data and all that has come to light over recent years, that something is rotten in the state of Denmark. The unclear criteria and “windows” opened by the law obviously allow those with financial means to be released from prison quite easily. If the Floros case had not arisen, the situation would have been perpetuated, with no reaction.

It is self-evident that our prisons need to become more human, and that the industry of prison releases must be dismantled. Prisoners who are demonstrably suffering should have the necessary care and enjoy the benefits of the law.

However, stable rules are needed, with unassailable criteria that will allow no one to circumvent them.

The Paraskevopoulos law does not appear to meet that standard, even with its recent amendment.

If that is not done, the fears and insecurity of citizens will be aggravated, and the endurance of institutions and the rule of law will be questioned.